Listen up, I’m inventing a genre.

I don't know what genre my actual band, The Indelicates, are. Probably Art Rock, but that makes us sound like the wankers we are so I resist it. At any rate, we are all over the map musically, which is all well and good - but it doesn’t let you create a genre.

There is something wonderfully biological about finding a niche between the bifurcating taxonomies of music and twisting what exists just far enough that it reaches the point of speciation.

Electric guitars are fine, but it turns out that there is a point where you have heard enough of them and ever since this happened to me all my favourite music has been the kind of stuff that has a really juicily specific genre attached to it.

Sissy Bounce, for example. Sissy Bounce is the greatest. Sissy Bounce is when you take the high tempo, hyper masculine barking Hiphop of New Orleans and have it performed by extremely LGBT people like Big Freedia and Sissy Nobby. Like this, check it out:

Or Truck Driving Country - sad semi-spoken country ballads that tell stories about Trucking, often including encounters with the ghosts of Truckers like in Phantom 309:

In a way, the ability to identify genres like this is one of the very few good things incentivised amid the music industry’s assimilation by centralised streaming giants. The economics of streaming have created a relentless churn of single tracks created in the hopes of finding their way onto highly subscribed playlists1. This is, generally, a bad thing - especially if you like the idea of whole albums that aren’t by Taylor Swift - but it’s great for the taxonomical proliferation of genres.

Before Spotify adding Japanese anime chiptunes to Future Bass records would have been a solitary pursuit - now Spotify has a Kawaii Future Bass playlist for the world to listen to. Which is nice.

Anyway. I’m inventing a genre. It’s called Happy Hauntology. This post is to propose it, to invite you to make it and to describe what it is so that you know it when you hear it.

Hauntology, the wider genre of which Happy Hauntology is a subgenre, was originally coined as the name for a field of academic study by Jacques Derrida. He, in turn, took it from the opening line of The Communist Manifesto which states: “A spectre is haunting Europe - the spectre of communism”.

The literary criticism that Derrida and his cohort engaged in sought to ‘deconstruct’ texts by identifying moments of tension, ambiguity and internal contradiction within them and, by teasing these discordant factures apart, to undermine the basis by which ‘meaning’ was commonly understood as a straightforward and objectively discoverable feature of reality. The tension in the first line of the communist manifesto was readily apparent and ripe for teasing. Why a spectre? Why haunting?

The ordinary reader (that’s you) might assume that the flowery language was chosen by the non-native speakers Marx and Engels as a slightly adolescent literary flourish - but to a big old French deconstructionist like Derrida every such authorial choice was pregnant with unconscious meaning. The authors might not have intended to evoke the panoply of associations that came with the mention of spectres and hauntings - but they had still done so and now those meanings were loose about the manifesto like mischievous demons summoned by an accidental recitation of Latin found scribbled in a notebook in the basement of a cabin in the woods.

And of course, communism hadn’t quite gone to plan. Derrida coined Hauntology in his 1993 book Spectres of Marx - four years on from the wave of counter-revolutions that had swept eastern Europe and set in motion the fall of the Soviet Union. The academy found itself at the start of the current intellectual era wherein the economic theory that had dominated a significant percentage of its outlook in every branch of the humanities had been, in the eyes of the world, discredited by history. Marxism informed every branch of theory - not just economics. The ideology’s reputation had died a slow death in the Cambodian killing fields, in Hungary, in Prague, Tiannenmen Square - but its ghost, that spectre unleashed by two men in their twenties proving careless with their metaphors, continued to haunt the common rooms and institutes of Europe.

Hauntology, then, in Derrida’s conception, was the study of the way that the dead past continued to influence the present in the same way that dead bastards continue to influence 1970s council houses. Marxism was ‘dead’ but its ghost was omnipresent in the Western mind.

He intended the word as a joke. If you say Hauntology in a comical French accent (perhaps while brandishing some garlic on a rope) it sounds indistinguishable from Ontology - the study of what it means for a thing to ‘exist’ - and while this is perhaps less immediately hilarious in an English accent, you can see what he was getting at.

In the second half of the 2000s, critics like Mark Fisher and Simon Reynolds reacted to music by Burial, The Caretaker, Braodcast and Boards of Canada (The sort of thing they used to play on Blue Jam and in the background of Salad Fingers cartoons) by using Hauntology explicitly as a genre name for the first time. Fisher described how

Sonically, their music typically mixes digital and analog: samples and computer-edited material mingle with antique synthesizer tones and acoustic instruments; motifs inspired by/stolen from library music and movie scores (particularly pulp genres like science fiction and horror) are woven together with industrial drones and abstract noise; and there’s often a musique concrete/radio-play element of spoken word and found sounds.

The effect of such records was to provoke a particular kind of unsettling nostalgia. The music was haunted by the intrusion of the past into present, as though brushed with the spectral fingers of a future that had gone differently from between the dimensional void. The term had moved on from Derrida’s lost Marxist utopia to a more parochial and emotionally potent lost future extrapolated from Ballroom dances and desolate sonic wastelands in the US and, in the UK, from the kind of synthetic music that used to play over the top of public information films and children’s educational programming.

The absolute leaders in this new style were the various incarnations and musical groupings released by Ghost Box Records - in particular those under the names The Focus Group and Belbury Poly. Their work was (and still is) the platonic form of British Hauntology - brilliantly conceived and executed and with enough humour mixed into it to avoid the slightly ponderous excesses of the gloomier parts of the hauntology spectrum. Take this, for example, from 2012:

See?

The Hardcore music that emerged in the early 90s in the BeNeLux countries is a fast, aggressive form of dance music full of distorted synths and absent the healthiest of attitudes. This sort of thing:

The UK’s chemically ecstatic rave scene’s answer to grimdark hardcore was Happy Hardcore a genre variant that kept the speed and brashness of dutch Gabber but added wistful chord sequences, positivity and girls - as in this:

This, along with the development Happy Jungle, Happy House and (even) Happy Metal established the convention of using Happy as a modifier when speciating a new genre that lightened up a previously existing one.

Nearly there. one more thing.

Disneyland’s Haunted mansion - one of Theme Park design’s true masterpieces - begins by having guests wait in a small antechamber before being ushered into an octagonal room with portraits hung on each wall. After a moment to ensure everybody is safely within, the room stretches. Looking up you can see the ceiling queasily moving away from you as the mechanism operates smoothly and slowly enough that it isn’t readily apparent whether the floor is descending or the roof rising2. The portraits expand to reveal hidden details - a woman with a dainty parasol is revealed to be perched precariously above a snapping crocodile, a Victorian gent in a suit is standing in his underpants on top of a barrel of dynamite with a lit fuse etc - and, over hidden loudspeakers, perhaps the most iconic voice-over in Theme Park history plays, culminating in the attraction’s main hook:

There are several prominent ghosts who have retired here from creepy old crypts all over the world. Actually, we have 999 happy haunts here — but there’s room for 1,000. Any volunteers?

Happy Haunts! That’s literally the name that Disney uses for its ghosts! OMFG.

I wrote my solo album Arcadia Park during the latter half of the pandemic. The idea was to write the soundtrack album for the fictional theme park I’d been visiting in my head once worshipping pylons got old. It ended up being one of the most profitable musical projects I’ve ever been involved with, but that story is long and weird and hilarious, involves the NFT boom, a mysterious (now notorious) crypto anon and a conceptual law professor who makes art by writing legal letters to the SEC. It will have to wait for it’s own Substack post someday. What I will tell you is that it is a double album of background music that soundtracks an imaginary theme park dedicated to Faeries, Space Travel, Dinsoaurs, Tiki Gods and Good Old American Progress.

As with traditional Hauntology, I wanted to create an informational artefact that felt like it had fallen through a wormhole from some other place. I wanted it to dislocate the listener in that same hauntological strange semi-nostalgia for a lost future extrapolated from the sounds of a 1980s childhood. But the end result was not intended to be disquieting or disturbing. Like The Haunted Mansion, Arcadia Park was a place of comfort - even joy. It was not the unsettling experience of being spooked and tormented by the ominpresence of a dead past, but the reassuring experience of reflecting on the lost retro-future of the arificial past promised by the Epcot Center in 1990.

Jean Baudrillard discussed the Disney theme parks in his 1995 book Simulacra and Simulation. Identifying the theme park as a perfect simulacrum - a copy of a thing for which there is no original - he describes how

Disneyland is a perfect model of all the entangled orders of simulacra. It is first of all a play of illusions and phantasms: the Pirates, the Frontier, the Future World, etc. This imaginary world is supposed to ensure the success of the operation. But what attracts the crowds the most is without a doubt the social microcosm, the religious, miniaturized pleasure of real America, of its constraints and joys. One parks outside and stands in line inside, one is altogether abandoned at the exit.

The most interesting thing about this, of course, is the fact that Jean Baudrillard definitely went to Disneyland at some point. I hope that you, too, are imagining him sat in one of the little boats on Peter Pan’s Flight eating a choc ice shaped like Mickey Mouse just absolutely having the worst time.

The second most interesting thing is the way that it points to a subtly different but equally compelling basis for hauntologically inspired musical texts. Like the 999 Happy Haunts - those friendly revenants of the never living - we can propose Happy Hauntology: where Hauntology evokes the ghosts of a past that died, Happy Hauntology evokes the sprites of a past that never happened.

Happy Hauntology imitates the conventions of Disneyland’s simulacra - its Pirates and Future Worlds and its accompanying ballads of progress through global unity - and knowingly creates yet another level of abstraction: a counterfeit of a counterfeit of a confection.

After announcing Arcadia Park, I found out that - almost exactly like with Leibniz and Newton’s simultaneous creation of the calculus - the artist Laurence Owen whom I used to drag around Europe playing bass parts that were beneath his talent as part of The Indelicates had also recently released the soundtrack to a fictional theme park and that it was annoyingly brilliant.

And with those two albums, frankly, I think that’s enough to declare a genre. And to state these Articles:

Happy Hauntology is haunted less by the ghosts of economic utopias unrealised but by the happy haunts of vacations never taken.

Happy Hauntology draws from exotica, retrofuturism, electronica, MOR and Surf Rock to create a tapestry of themed music that is preoccupied with surface and music as the textural substrate of spectacle.

Happy Hauntology is the soundtrack to invented memories of magical man-made places.

Happy Hauntology is created in a box with technologies that counterfeit the analogue.

Hauntology’s key musical touchpoints are the following:

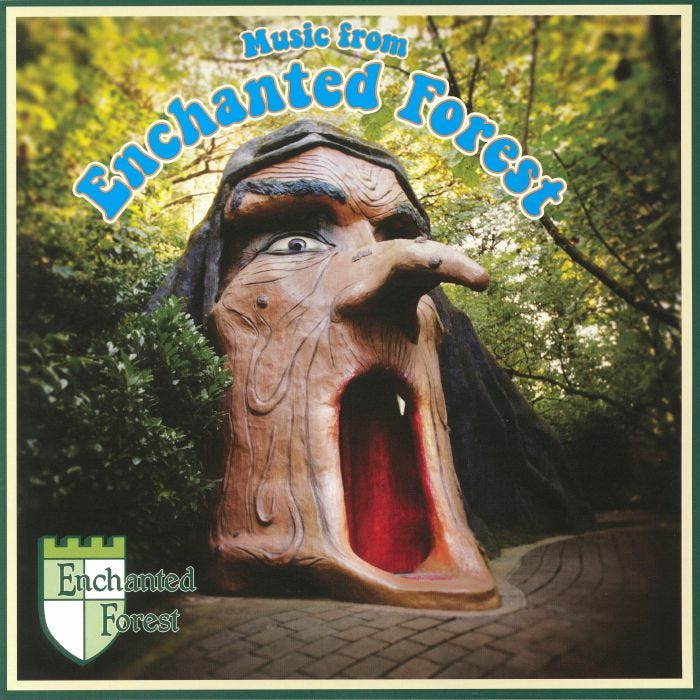

Music from Enchanted Forest by Susan Vaslev

Pardoes Promenade and De Vliegende Hollander from the Efteling Soundtrack

Space Mountain and The Tiki Tiki Tiki Tiki Tiki Room from Disneyland

Horizons from Epcot

And dear god, The Main Street Electrical Parade most of all.

Happy Hauntology requires lore.

Please make Happy Hauntology and upload it to the internet and if you hear of any, please tell me about it. I will not rest until there is a dedicated Spotify playlist. To all that come to this happy place, welcome.

You can listen to Arcadia Park in full on Spotify or find it on whichever platform you prefer to use to fuck musicians over. This is from it:

You can even spend an hour exploring the park in text adventure form here:

https://visit.arcadiapark.xyz/

Just ignore the NFT stuff and go straight through the gate - you have access to almost everything as a guest.

I’m still not sure what this substack is. This one is definitely quite freewheeling, but maybe this is a good place for that? IDK. Maybe I boxed myself in by leaning extra heavily on the theme park angle? I’m not sure how much more I’ve got to say about them beyond that they are ace. Should I do my top ten rollercoasters? Who knows. Julia finally recorded the last bit of singing on our new Indelicates studio album. Maybe there will be stuff to say about all of that. Weird tangential comments are appreciated.

This model is already being devoured by TikTok’s insistence on single hooks that have been sped up so that people can use them as backing tracks for impenetrable Gen Z jokes - but I am far too old to have a complicated opinion about that.

It is, in fact, one way in California and Paris and another in Florida. Good magicians often perform the same trick with different methods.

I think I just stumbled upon some Happy Hauntology in the wild. Or at least some HH adjacent stuff. This guy named Michael Hearst has an album of songs for ice cream trucks, an album of songs for weird vehicles, an album of songs for unusual animals, etc.

https://michaelhearst.bandcamp.com/album/songs-for-ice-cream-trucks

It certainly sounds to me like the kind of aesthetic you're describing. He seems to largely be using analog instruments and not digital replicas thereof so perhaps that's a disqualifier. Thought it was worth a mention at least.

I've been trying to come up with an HH project for my band to have a go at and I think I figured it out. I'm going to try and craft the soundtrack for a psychedelic sixties sci-fi b-movie!

Wish me luck!

Oh my god, finally someone else who has had this same idea in their brain, but articulates it much more clearly. I've been calling this type of music "EPCOTcore" in my brain. I think the one thing that differentiates in my mind from say, other retrofuturism genres is probably the *wistfulness*. Many of them are valid critiques of unfettered technoutopianism, but too much of that feels so depressing. I want more media that channels the inner child back to what it felt like as an 8 year old going to a science museum, all these weird wonders that we as humanity are using our collective effort in order to figure out [1][2].

Tangentially, I feel like the same emotions surface in genres such as MIDI Music[3]. Instead of the deconstruction of 90s corporate music that Vaporwave was, it's a celebration of the "Ringtone Bangers"[4] - your catchy ringtones that upon another listen, are actually quite joyful.

[1] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jR0vRuZkxdw

[2] https://lapfox.bandcamp.com/track/welcome-home-2

[3] https://sexytoadsandfrogsfriendcircle.bandcamp.com/album/staffcirc-vol-9-midi-module-fanatix

[4] https://www.youtube.com/c/ringtonebangers